The Midnight Ride of William Dawes?

Few Americans would fail to recognize the first few lines of the Longfellow poem:

Listen

my children and you shall hear

Of the midnight

ride of Paul Revere,

On the eighteenth of April,

in Seventy-five;

Hardly a man is now alive

Who

remembers that famous day and year

Here is the rest of the story.

Samuel

Adams and John Hancock were wanted men. In mid-April of 1775, they were secreted

away in the parsonage of Rev. Jonas Clarke in Lexington, Massachusetts while on

their way to Philadelphia and the Second Continental Congress, which was to convene

on May 10 of that year. General Thomas Gage, the British commander in Boston,

had two reasons for marching westward toward Lexington. One was to capture a supply

of arms and powder that his spies had told him might be there. He was more confident

that arms would be found farther down the road in Concord. He also wanted to seize

Adams and Hancock. On the evening of April 18, he sent his army across the Charles

River to begin the long march.

Paul Revere had arranged for signals to be briefly

displayed in the bell-tower of Boston's Old North Church and the local Sons of

Liberty recognized that two lanterns meant that Gage's troops were to cross the

river. Revere was already on the other side, in Charlestown, when he heard the

news. He began to give the alarm as he rode through Medford and Menotomy (now

Arlington) and other small villages along the way. On orders from Dr. Joseph Warren,

a leader of the  Sons

of Liberty, William Dawes took the longer

Sons

of Liberty, William Dawes took the longer  route

through Boston Neck, shouting to everyone within earshot, "The Regulars are

out!" After meeting Dawes in Menotomy, Revere entered Lexington only a few

minutes ahead of his comrade, quickly warning Hancock and Adams. Dr. Samuel Prescott,

courting a young lady in Lexington (Lydia Mulliken), decided to join the other

two in riding on to Concord, where another cache of arms was stored.

route

through Boston Neck, shouting to everyone within earshot, "The Regulars are

out!" After meeting Dawes in Menotomy, Revere entered Lexington only a few

minutes ahead of his comrade, quickly warning Hancock and Adams. Dr. Samuel Prescott,

courting a young lady in Lexington (Lydia Mulliken), decided to join the other

two in riding on to Concord, where another cache of arms was stored.

On

their way to Concord, the intrepid trio soon encountered a roadblock manned by

4 British soldiers and tried to overpower them by riding through them. Prescott

and his steed jumped a stone wall and escaped. Dawes and Revere both regained

their freedom, but their success was extremely short-lived. They were soon confronted

by 6 Regulars at another roadblock. While Revere was being arrested, Dawes escaped

again and returned to Lexington. After his fortunate escape, Dr. Prescott went

on to  notify

the residents of Concord of what was happening.

notify

the residents of Concord of what was happening.

The church bell was rung and the militia met on Lexington Common to the beat of 16 year-old William Diamond's drum (born July 20, 1758) and the peal of 17 year-old Jonathan Harrington's fife. Captain John Parker assembled the men of the town and there they waited in dawn's early light for their appointment with destiny. While they waited, the fifer and drummer played tunes that the men all knew and some of them sang along. One song probably played was Chester. Written by William Billings, a leather tanner from Boston, it was one of the most popular songs of the entire war.

Let

tyrants shake their iron rods,

Let

slavery clank her galling chains.

We

fear them not! We trust in God!

New

England's God forever reigns.

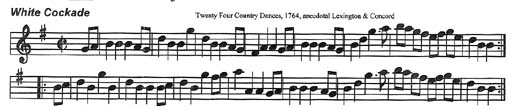

Revere was later released but, having no horse, had to walk the rest of the way into Lexington, where he managed to witness the latter part of the battle. The total distance traveled was about 13 miles. Hancock and Adams made a hasty exit, roamed around Massachusetts for a while, then went on to Philadelphia. At about noon, Diamond and Harrington led the march of the Lexington militia on to Concord. One of the tunes they played was the White Cockade (My Love was Born in Aberdeen)..

Flag

carried by Bedford Minutemen at Concord

In June, 1775, Diamond led the Lexington militia to the Battle of Bunker Hill (Breed's Hill). He later became a foot soldier and served for the duration of the war. He was present at the British surrender at Yorktown. He died on July 29, 1828 and is buried in Petersborough, New Hampshire. The fife playing Harrington is not to be confused with his cousin, also Jonathan Harrington of about age 30, who was mortally wounded in the first British volley and died in the arms of his wife on his doorstep. The younger Harrington was the last survivor of the Battle of Lexington and died in 1854.

On April 19, a far more impressive ride was begun by a man whose name is all but lost to history. Israel Bissell was a postal rider who normally carried mail from Boston to New York. He was ordered to take the news of Lexington "quite to Connecticut" by his commander, Col. Joseph Palmer of Braintree. Bissell rode harder than he ever had in his life. He was in Worcester in two hours. It is said that it was there that his horse died beneath him. He got a fresh mount and was in New Haven, Connecticut by April 21. He arrived in Manhattan on April 23, shouting the news of Lexington and Concord.

One would think that he had more than fulfilled his orders at this point but Bissel carried on through New Jersey, finally ending his marathon ride in Philadelphia on April 25. He had ridden about 320 miles from his starting point in Watertown, Massachusetts. No one knows if he slept along the way. He now rests in Hinsdale Cemetery, Hinsdale, Massachusetts.

PS. No one knows the where the term, "The British are coming!" came from. It didn't derive from Longfellow. If someone rode into your town tonight shouting, "The Americans are coming!," you would probably roll over and go right back to sleep. Everyone was British. "The Regulars are out!" would have gotten instantaneous results. - E.B.

PPS. William Dawes' great-grandson, Rufus R. Dawes, served in the Union Army during the War Between the States. As a Lt. Colonel in the 6th Wisconsin, he led the successful defense of Culp's Hill at the Battle of Gettysburg. His son, Charles G. Dawes, became the 30th Vice President of the United States under Pres. Calvin Coolidge, later sharing the Nobel Peace Prize.

ŠE.W.Boyle, 2001 (All Rights Reserved)